by Ishani Agnihotri

Introduction

The first programmable digital computer, Colossus, was invented by British codebreakers in the 1940s during World War II. This machine, rooted in abstract mathematical reasoning, inspired Western scientists to explore the concept of creating an “electronic brain.” These advancements laid the groundwork for Artificial Intelligence (AI) research, formally established at Dartmouth College in 1956.

While these developments marked the onset of technological revolutions in the Global North, newly independent nations in the Global South grappled with sovereign, economic, and social challenges. In contrast, the Global North’s stable political systems, robust economies, and advanced human capital fostered superior research and development – positioning the Global North to lead and the Global South to follow in shaping the future technological revolutions.

The rise of AI is one such technological revolution. The current AI boom brings forth opportunities to transform economies, societies and regions, akin to the internet. However, historical infrastructural gaps, divergent socio-economic priorities, and the persistent digital divide between the Global North and the Global South risks the latter being underrepresented in the development and benefits of AI – A risk highlighted in the often biased, unrepresentative, and stereotyped AI models, often trained on Western-centric data and deployed in the Global South – thereby exacerbating existing inequalities.

What is AI Data Ecosystem

An AI data ecosystem is an interconnected network of individuals, processes, technologies, and infrastructures that facilitate the collection, storage, sharing, and utilisation of data to enable AI capabilities.

Data is a foundational element for development of any AI ecosystem. The quality and quantity of data determine the performance, accuracy and reliability of AI models. These models are trained on extensive datasets to learn and make precise predictions or decisions. Additionally, data plays a vital role in testing and evaluating the effectiveness of trained AI models, ensuring their practical applicability and robustness.

A robust data ecosystem encompasses infrastructure for capturing, storing and organising data, data pipelines, governance frameworks, and tools and capacity for data analysis and management. To ensure viability and scalability of such systems, a strong economic, physical, technological, and data governance capacity is imperative.

The Over-Representation of Western Data in AI Data Ecosystem

Much of the data used to train AI models today originates from Western contexts, reflecting the cultural norms, societal structures, and economic priorities of developed nations. This over-representation creates a bias in AI systems, which often struggle to generalize effectively to diverse global contexts, particularly in the Global South.

Instances of cultural misrepresentation highlight these biases. For example, when asked to generate images of German soldiers from 1943, Google’s Gemini AI stirred a controversy by creating some images depicting people of African and Asian descent in Nazi uniforms. Similarly, when prompted to depict ‘a day in Delhi’, ChatGPT produced outdated stereotypes, showing a mid-century town with men in turbans selling vegetables and women with covered heads.

Beyond stereotyping, Western-centric datasets constrain AI benefits to what can be termed a ‘White Man’s World.’ For instance, AI tools for disease diagnosis, such as those for skin cancer detection, often underperform on patients with darker skin tones. Facial recognition systems, trained predominantly on lighter-skinned datasets, frequently misidentify individuals of African or Asian descent at higher rates than those of European descent.

This AI data disparity is rooted in several structural advantages enjoyed by the Global North. Developed nations in the Global North, buoyant with public and private investments, and historical lead, continue to remain leading technical centres with concentration of data collection and research infrastructure. Programs like the U.S. National AI Initiative and the European Union’s Horizon Europe allocate billions of dollars for AI research, infrastructure, and innovation. The United States hosts six of the top ten global data centres projects, providing scalable infrastructure for storing and processing large datasets.[i] Supercomputers such as Frontier (USA) and Fugaku (Japan) further enhance their data processing capabilities. In addition, tools like TensorFlow, PyTorch, and JAX, developed in the Global North, empower these nations to lead in creating and curating datasets, thereby influencing the training of AI systems.

In addition to advanced technologies, Global North nations also lead in setting global benchmarks for data protection and governance. Frameworks such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the OECD AI Principles, and robust intellectual property laws reinforce their dominance.

The Missing Case of Global South Data

The Global South, characterized by its rich cultural, linguistic, and societal diversity, holds immense potential as a source of untapped data and an emerging AI market. Indigenous communities in these regions offer valuable traditional knowledge in agriculture, medicine, and environmental management, which could drive the development of specialized AI models for global applications. For example, AI tools for tuberculosis detection and management, trained on Global South Data, could address the needs of over 6 billion people – more than 85% of the global population.[ii] Similarly, pest detection and management tools, tailored to tropical climates and regional agricultural practices could support 73 percent of global agriculture production.[iii]

Despite the potential, the development of Global South data ecosystem is fraught with challenges. The historical digital divide and digital literacy disparity is keeping the region from attracting investments and innovation tantamount to technological centres of the Global North. It is to be noted that in 2023, the USD 67.2 billion AI private investments made in the United States was roughly 48 times greater than the amount invested in India (USD 1.39 billion) – the only Global South country which made it to top ten leading list of countries in terms of private investments in AI by geographic area.[iv]

Beyond the historical geo-politico-economic inequalities, there exist a set of geopolitical and socio-economic factors internal to Global South countries, which mar their potential of developing a robust AI data ecosystems. Unstable political systems, frequent protests, border conflicts, and reactionary trade policies deter technological innovation and competitiveness in regions like South America and South Asia. For example, countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan or Sri Lanka exhibit dwindling state capacity, low skill availability, and inadequate digital infrastructure, translating into low technological investment potential. Weak regional economic linkages further limit this potential.

In addition to politico-economic conflicts, demographic and geographic challenges such as high population growth, resource scarcity, and vulnerability to climate extremes exacerbate issues like poverty, hunger, and large scale migrations. These challenges divert attention and resources away from technological advancements, creating institutional priorities distinct from those of the Global North.

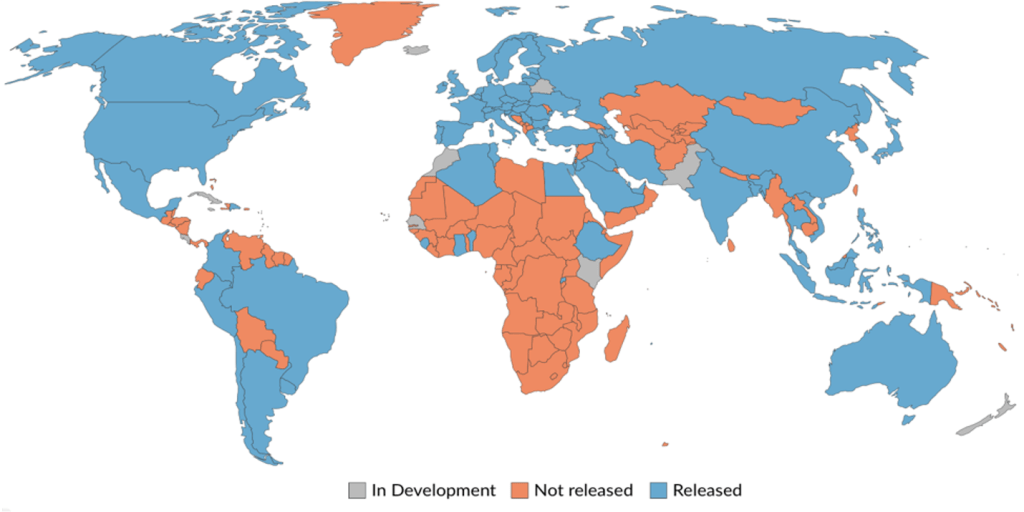

Countries with National Artificial Intelligence Strategies, 2023 [v]

A combination of these interconnected factors have resulted in a relatively slower pace of digital infrastructure growth, inadequate data governance policies, and underdeveloped data ecosystems in the Global South – restricting the ability of the Global South countries to contribute meaningfully to the global AI data ecosystem. As a result, the unique socio-economic, linguistic, and cultural realities of these regions are often overlooked or misrepresented in AI systems.

Steps Taken by Global South Countries

Despite political and infrastructural challenges, several Global South nations are taking proactive steps to harness their unique data potential and contribute to AI development.

The Government of India’s Bhashini Platform, offers an example of the challenges and the opportunities involved in developing natural language processing (NLP) tools that fit a local context.[vi] This initiative aligns with India’s vision for developing ‘AI for all’, which has attracted private investments worth USD 1.4 billion and earned the country a 10th-place ranking in the Stanford AI Index 2024.

Several grassroots initiatives like Masakhane or the Makerere Artificial Intelligence Lab in Uganda focus on creating datasets and language models for low-resource African languages, promoting African representation in AI.[vii] [viii] Partnering with Microsoft, Nigeria, under the Digital Nigeria eLearning Platform, is working towards enhancing its digital literacy to empower its population for AI-driven opportunities.[ix] However, to be able to better influence and reshape the ongoing AI revolution towards inclusivity and representativeness, a more holistic participation of the Global South countries is required.

Putting the Global South on AI Data Map: Way Forward

The data rich potential of otherwise data poor countries of the Global South needs to be realised. To achieve this, three steps could be considered to set the global AI journey on the path of inclusivity.

1. Promote Skill Development for Sustainable Growth:

To avoid the risk of becoming low-skilled and medium technology hubs for data labelling and correction – a trend being observed in Global South countries, investments need to be made towards developing sustainable talent pipelines. This requires active collaboration between local governments, international aid organizations, and private entities to enhance local capabilities.

For example, the German Development Cooperation initiative ‘FAIR Forward – Artificial Intelligence for All’ has partnered with seven countries: Ghana, Rwanda, Kenya, South Africa, Indonesia, Uganda and India, to improve access to training data and develop local AI and machine learning capacity.[x] Similarly, by equipping workers with workplace skills, Microsoft, at the Africa Development Centre, is strengthening Africa’s talent pipeline, ensuring long-term benefits in the AI value chain.[xi]

2. Micro Data Centres:

Micro Data Centres (MDCs) offer scalable and cost-effective solutions to address the unique challenges faced by the Global South, including connectivity, data sovereignty, and localized computing needs. These small facilities are designed to handle critical processing workloads with reduced space and investment requirements, making them ideal for the region.

MDCs align with the lower capital and operational costs found in Tier II, III, and IV cities, which are experiencing increased demand for edge computing and local capacity. A research paper by People + AI suggests that an investment of ₹60 crore in an MDC could yield returns up to three times greater than traditional data centres.[xii] Furthermore, the potential of green MDCs, powered by renewable energy, offers a compelling economic model for climate-sensitive regions in the Global South.

With reduced latency and improved access to AI services, MDCs have significant potential in sectors like healthcare, banking, financial services, insurance (BFSI), and large-scale government operations across the Global South.[xiii]

3. Building Data Partnerships and Value Chain Development:

Regional data partnerships and value chain development can accelerate growth by fostering knowledge exchange, resource sharing, and strategic collaboration. Programs like “Make Inclusive Data the Norm” in Colombia, Kenya, and Ghana leverage citizen-generated data to represent marginalized groups in policymaking.[xiv] Strategic regional partnerships also enhance the technological bargaining power of the Global South countries. For example, under India-UAE Deep Tech Cooperation, both nations are jointly exploring the technical and investment potential of developing data centre projects in India with initial capacity of up to 2 GW.[xv]

Such strategic partnerships also create opportunity for development of regional data and technological frameworks to address common challenges and safeguard regional interests. Regional frameworks like the ASEAN Data Management Framework and Model Contractual Clauses for Cross Border Data Flows (MCCs) promote digital integration and reduce compliance costs for businesses engaging in data management and cross-border data activities, thereby enhancing the region’s technological potential.[xvi] [xvii]

By focusing on these three steps, countries in the Global South can unlock their data potential for greater participation in the global AI ecosystem. This will not only empower local communities but also contribute to a more inclusive technological landscape globally – aligning the needs and opportunities of the Global South with the priorities of the Global North for developing AI as a truly global technology.

References

[i] Amber Jackson, (2024, August 14), Top 10 biggest data centre projects, Retrieved from Data Centre Magazine: https://datacentremagazine.com/top10/top-10-biggest-data-centre-projects, Accessed on December, 2024

[ii] World Economics, (2025, January), Global South, Retrieved from World Economic: https://www.worldeconomics.com/Regions/Global-South/, Accessed on December, 2024

[iii] United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), (2024, September), Global changes in agricultural production, productivity, and resource use over six decades, Retrieved from USDA: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2024/september/global-changes-in-agricultural-production-productivity-and-resource-use-over-six-decades/, Accessed on December, 2024

[iv] Stanford University, (2024), AI Index Report 2024, Retrieved from Stanford University: https://aiindex.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/HAI_AI-Index-Report-2024.pdf, Accessed on December, 2024

[v] “Data Page”: Countries with national artificial intelligence strategies”, part of the following publication: Charlie Giattino, Edouard Mathieu, Veronika Samborska and Max Roser (2023) – “Artificial Intelligence”. Data adapted from AI Index. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/national-strategies-on-artificial-intelligence , Accessed on December, 2024

[vi] Press Release (2022, May 22), Press release on digital initiatives, Retrieved from Press Information Bureau (PIB): https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1827997, Accessed on December, 2024

[vii] Masakhane, https://www.masakhane.io

[viii] Artificial Intelligence Research (AIR) Uganda, https://air.ug

[ix] Dayo Ayeyemi, (2024, October 2), Microsoft, FG partner to boost digital transformation, Retrieved from Tribune Online: https://tribuneonlineng.com/microsoft-fg-partner-to-boost-digital-transformation/#:~:text=He%20said%2C%20“the%20programme%20has,the%20Digital%20Nigeria%20eLearning%20Platform, Accessed on December, 2024

[x] BMZ Digital, Fair Forward: Artificial Intelligence for All, Retrieved from https://www.bmz-digital.global/en/overview-of-initiatives/fair-forward/

[xi] Microsoft Africa Development Center, Retrieved from https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/madc?oneroute=true

[xii] People + ai, (2024, September), Micro is the new mega – a note on micro data centres prepared by people+ai, EkStep Foundation, Retrieved from https://ff695b5dd2960f41cb75835a324f0804.r2.cloudflarestorage.com/drp-cl/e4247405-8bb6-453d-afd5-c0f4c82093f9/8994e0cb-7990-465a-9395-6fa61f0a0b65/cb3d5330-d461-4ccd-9acd-b0d31329654d.pdf?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=fed7aac277aea51eca0c294ada409f61%2F20241229%2Fauto%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20241229T085929Z&X-Amz-Expires=3600&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Signature=f5878c630db903a886152951706d3e5a62121d83609c239f2a5f6367951799a1, Accessed on December, 2024

[xiii] Suraksha P, (2024, September 23), India hosts fewer than 10 micro data centres: paper. Retrieved from Economic Times: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/technology/india-hosts-fewer-than-10-micro-data-centres-study/articleshow/113575415.cms, Accessed on December, 2024

[xiv] Eleonora Betancur, Director, APC Colombia Claire Melamed, Director, The Global Partnership, (2024, June 28), Global South leading the way on citizen-generated data. Retrieved from Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data: https://www.data4sdgs.org/blog/global-south-leading-way-citizen-generated-data, Accessed on December, 2024

[xv] Press Release, (2024, February 14), UAE, India sign MoU to accelerate growth in digital transformation. Retrieved from Emirates News Agency – WAM: https://www.wam.ae/en/article/b1ns93x-uae-india-sign-mou-accelerate-growth-digital, Accessed on December, 2024

[xvi] ASEAN Data Management Framework. Retrieved from https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/ASEAN-Data-Management-Framework.pdf

[xvii] ASEAN Model Contractual Clauses for Cross-Border Data Flows. Retrieved from https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/3-ASEAN-Model-Contractual-Clauses-for-Cross-Border-Data-Flows_Final.pdf

About the Author

Ishani Agnihotri holds a Master’s degree in Politics (International Relations) from Jawaharlal Nehru University and a B.Sc (Hons) in Mathematics from Kirori Mal College, University of Delhi. With over two years of working in policy space, particularly in tech policy roles, Ishani is enthusiastic about safe and equitable access to AI revolution for all.